storytelling is complicated, especially when you’re writing a video game with multiple, player-driven endings. no matter much work is done to keep their quality consistent, the reality of operating within the strict parameters of the good/bad scale traditional to the medium almost always means one is going to come out on top as the more fitting or satisfying conclusion.

take shūjin e no pert-em-hru, a freeware game developed in rpg maker dante 98 ii and released in 1998 for the pc-98. pert-em-hru — or peret em heru: for the prisoners, as it was dubbed by a 2014 fan translation — follows a group of japanese tourists conscripted by an unsavory archaeologist and his medical student assistant to explore the great pyramid of giza in egypt. the player is put in control of high school student ayuto asaki, the group’s scout and de factor leader, as he struggles to survive the pyramid’s traps and keep everyone alive.

pert-em-hru gives the player a variety of verbs to use on the world around them in-between almost meaningless random battles against wild animals and, later, supernatural foes. by the end of the game, ayuto can recruit party members, push, pull, shout, crouch, take, and look up, all of which are used at crucial moments in the story to advance the plot or, more importantly, save someone in the tour group from a grisly death. it’s these moments of puzzle-solving that decide how pert-em-hru‘s finale plays out.

after a few hours of adventuring, the party — at full strength thanks to ayuto‘s quick thinking, cut down by the pyramid’s violent tests, or somewhere in-between — reaches the ancient structure’s final chamber and confronts the mummified remains of khufu, the egyptian monarch for whom the tomb was constructed. khufu is still breathing, kept alive by some sort of magic until you put an end to his miserably long life. upon his death, the pyramid begins to crumble, forcing ayuto and his allies to hurriedly backtrack if they want to escape the ruins alive.

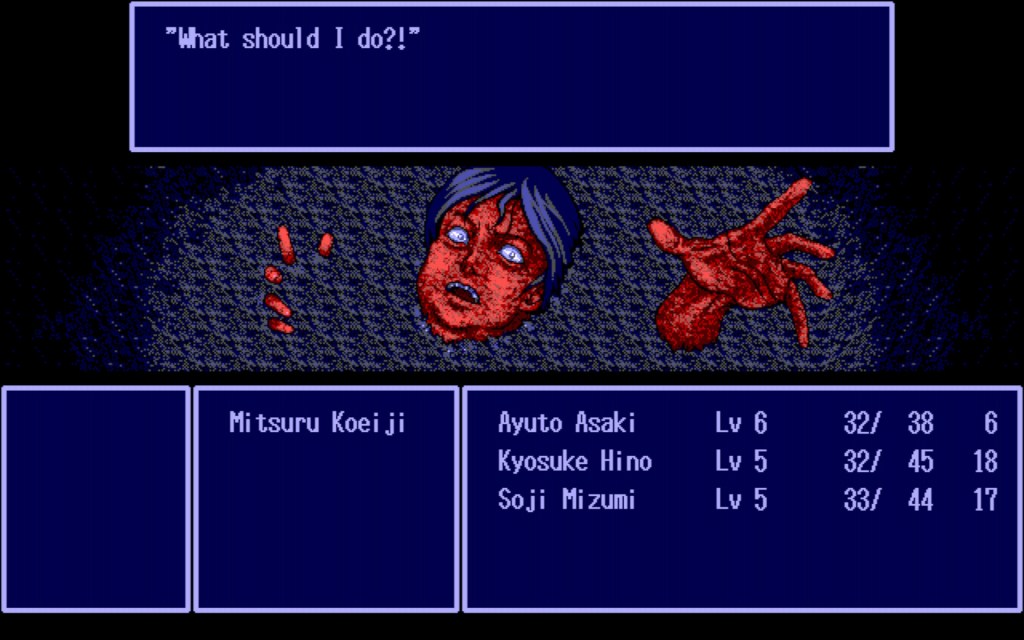

if you managed to save the whole party over the course of the game, this sequence is an expositional cakewalk that eventually concludes with pert-em-hru‘s “good” ending. everyone lives happily ever after and you’re rewarded with a sound test and some concept art. otherwise, the tour group members you lose return as enemies, gruesome reminders of your failure whose corpses must be desecrated further and killed permanently if you want to avoid suffering the same fate. earlier sections of pert-em-hru certainly don’t shy away from pixelated gore, but the bloody, close-up artwork of your mangled former allies featured in these battles still manages to be shocking.

it’s this distress that makes failure in pert-em-hru so compelling. the tour group is made up of well-written characters whose stories you can’t help but become invested in despite the game’s brevity. ayuto and his friend kyosuke hino are involved in a love triangle with classmate yoko nogisaka that becomes even more fraught when the threat of certain death is introduced. tour guide sae otogi moonlights as a drug smuggler, and seedy photojournalist soji mizumi threatens to expose her illicit activities unless she sleeps with him. saori shinoda carries a mysterious photo and threatens to harm herself at every turn. failing to save them is not only frustrating in an “i want to beat this video game” sense but heartbreaking in an “i want to save these people” sense as well.

imagine if mass effect 2, at the conclusion of its infamous “suicide mission,” reanimated any allies you may have lost and then forced you to put them out of their misery. sure, your choices during the mission may have inadvertently and indirectly gotten them killed in the first place, but it’s a different thing altogether to be told you now have to personally destroy the comrades with which you spent dozens of hours building complex, intimate relationships. pert-em-hru distills this hypothetical to just a few hours, but it’s no less impactful for being a smaller game with lower stakes and a no doubt miniscule budget compared to bioware‘s beloved space epic.

video game endings may often be labeled “good” or “bad” depending on their outcomes and overall vibes, but pert-em-hru‘s soul-crushing climax defies categorization. players are gifted through failure a more nuanced conclusion that forces them to contend with how their actions (or, in some cases, inaction) affect the game’s rich cast of characters. and for what it’s worth, i’ll always prefer a narratively satisfying ending over one in which you’re rewarded for simply being the best at completing the video game’s goals.